Battle of Matewan

| Battle of Matewan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| The People of Matewan | Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency | ||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Sid Hatfield Mayor Cabell Testerman† | Albert Felts† | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Deputy Fred Burgraff and a group of local miners and residents | 13 Baldwin-Felts Detectives | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3 killed; 2 Miners and Mayor Cabell Testerman | 7 killed; including 2 Baldwin-Felts Detectives brothers Albert and Lee Felts | ||||||

The Battle of Matewan (also known as the Matewan Massacre) was a shootout in the town of Matewan, West Virginia in Mingo County on May 19, 1920 between local miners and the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency.

A contingent of the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency arrived on the no. 29 morning train in order to evict families that had been living at the Stone Mountain Coal Camp just on the outskirts of town. The detectives carried out several evictions before they ate dinner at the Urias Hotel and, upon finishing, they walked to the train depot to catch the five o'clock train back to Bluefield, West Virginia. This is when Matewan Chief of Police Sid Hatfield decided that enough was enough, and intervened on behalf of the evicted families. Hatfield, a native of the Tug River Valley, was an adamant supporter of the miners' futile attempts to organize the UMWA in the saturated southern coalfields of West Virginia. While the detectives made their way to the train depot, the were intercepted by Hatfield, who claimed to have arrest warrants from the Mingo County sheriff. Detective Albert Felts then produced his own warrant for Sid Hatfield's arrest. Upon inspection, Matewan mayor Cabell Testerman claimed it was fraudulent. Unbeknownst to the detectives, they had been surrounded by armed miners, who watched intently from the windows, doorways, and roofs of the businesses that lined Mate Street. Stories vary as to who actually fired the first shot; only unconfirmed rumors exist. Thus, on the porch of the Chambers Hardware Store, began the clash that became known as the Matewan Massacre, or the Battle of Matewan. The ensuing gun battle left seven detectives and four townspeople dead, including Felts and Testerman. This tragedy, along with events such as the Ludlow Massacre in Colorado six years earlier, marked an important turning point in the battle for miners’ rights.

|

History

At the time, the United Mine Workers of America had just elected John L. Lewis as their president. During this period, miners worked long hours in unsafe and dismal working conditions, while being paid low wages. Adding to the dilemma was the use of company scrip by the Stone Mountain Coal Company, because the scrip could only be used for those goods the company sold through their company stores, thus the miners did not have actual money that could be used elsewhere. A few months before the battle at Matewan, union miners in other parts of the country went on strike, receiving a full 27 percent pay increase for their efforts. Lewis recognized that the area was ripe for change, and planned to organize the coal fields of southern Appalachia. The union sent its top organizers, including the famous Mary Harris "Mother" Jones.[1] Roughly 3000 men signed the union’s roster in the Spring of 1920. They signed their union cards at the community church, something that they knew could cost them their jobs, and in many cases their homes. The coal companies controlled many aspects of the miners' lives. [2] Stone Mountain Coal Corporation fought back with mass firings, harassment, and evictions. [3]

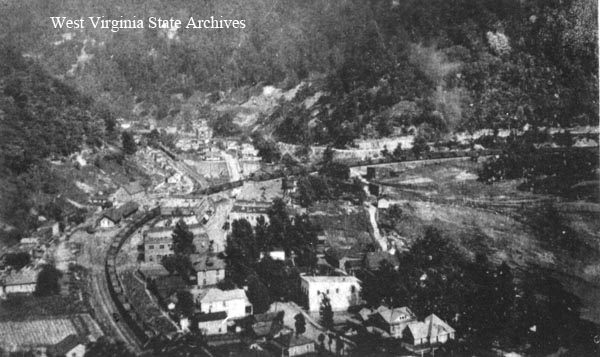

The Town of Matewan

Matewan, founded in 1895, was an small independent town with only a few elected officials. The mayor at the time was Cabell Testerman, and the chief of police was Sid Hatfield. Both refused to succumb to the company's plans, and sided with the miners. In turn, the Stone Mountain Coal Corporation hired their own enforcers, the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency, dubbed the “Baldwin Thugs” by the coal miners. The Baldwin-Felts Detectives had earned a reputation for their brutality. The coal operators hired them to evict the miners and their families from the company owned houses.[4] As a result, hundreds of miner families spent that spring in tents.

The Battle of Matewan

On the day of the fight, a group of the Baldwin-Felts enforcers arrived to evict families living at the mountain coal camp, just outside of Matewan. The sheriff and his deputy, Fred Burgraff, sensed trouble and met the Baldwin-Felts detectives at the train station. News of the evictions soon spread around the town. When Sid Hatfield approached Mr. Felts, Mr. Felts served a warrant on Sid Hatfield, which had been issued by Squire R. M. Stafford, a Justice of the Peace of Magnolia District, Mingo County, West Virginia, for the arrest of Sid Hatfield, Bas Ball, Tony Webb and others, which warrant was directed to Albert C. Felts for execution. The warrant turned out to be fraudulent. Burgraff's son reports that the detectives had sub-machine guns with them in their suitcases. Sid Hatfield, Fred Burgraff, and Mayor Cabell Testerman met with the detectives on the porch of the Chambers Hardware Store. It is still unknown whether it was Hatfield or the leading detective, Albert Felts, that shot Mayor Testerman first, though what followed was Sid Hatfield shooting Albert Felts. There are rumors that Sid shot mayor Testerman because he had feelings for his wife, but they were never confirmed, although he did remarry her after mayor Testerman's death. After the detective and mayor fell wounded, Sid kept firing, but Felts escaped. He took shelter in the Matewan Post Office, and Hatfield eventually found him there and shot him. When the shooting finally stopped, the townspeople came out, many wounded. There were casualties on both sides, including seven Baldwin-Felts Detectives, including brothers Albert and Lee Felts. One more detective had been wounded. Two miners were killed, Bob Mullins, who had just been fired for joining the union, and Tot Tinsley, an unarmed bystander. The wounded mayor was dying, and four other bystanders had been wounded.

Aftermath

Governor John J. Cornwell ordered the state police force to take control of Matewan. Hatfield and his men cooperated, and stacked their arms inside the hardware store. The miners, encouraged by their success in getting the Baldwin-Felts detectives out of Matewan, improved their efforts to organize. On July 1 the miners' union went on another strike, and widespread violence erupted. Railroad cars were blown up, and strikers were beaten and left to die by the side of the road. Tom Felts, the last remaining Felts brother, planned on avenging his brothers’ deaths by sending undercover operatives to collect evidence to convict Sid Hatfield and his men. When the charges against Hatfield, and 22 other people, for the murder of Albert Felts were dismissed, Baldwin-Felts detectives assassinated Hatfield and his deputy Ed Chambers on August 1, 1921, on the steps of the McDowell County Courthouse located in Welch, West Virginia.[5]. Of those defendants whose charges were not dismissed, all were acquitted. Less than a month later, miners from the state gathered in Charleston. They were even more determined to organize the southern coal fields, and began the march to Logan County. Thousands of miners joined them along the way, culminating in what was to become known as the Battle of Blair Mountain.

The Battle of Matewan

The Battle of Matewan occurred on May 19, 1920 in Matewan, a small town in West Virginia that lies along the Tug River that divides Kentucky and West Virginia. Mining and the coal industry dominated the lives of citizens in West Virginia. By 1900, coal became West Virginia's leading industry. The powerful coal companies controlled the lives of the miners. The coal companies owned the miners homes,required the miners to be patrons of the company stores.

The coal companies also had significant influence with politicians, newspapers and the school system. Coal companies controlled many aspects of life in Matewan. The miners worked long and hard hours while earning lower wages than they thought they deserved. There was a large wave of immigration in West Virginia in the late 1800's and early 1900's. Many workers from European countries, especially Italy, Hungary, and Poland worked in the mines. There was labor unrest throughout the country and this developed many labor disputes.

Much of the labor unrest was attributed to the transition from the country being a wartime economy to being a peacetime economy, the lack of jobs for soldiers that came back from the war, and the effects of the Bolshevik Revolution and Socialist Party. The country was a wartime economy during the war and now that the war ended, the country had to make the transition to a peacetime economy. There was the demobilization of armed forces and war industries. Also, the sudden cancellation of war contracts left workers and business leaders in a difficult plight to deal with the transition on their own. General labor unrest worsened the conflicts of postwar readjustment. Prices were rising, discontented workers (released from wartime constraints) were more willing to strike for their demands.

There were many strikes at the time. In 1919, over four million workers striked. Some in the East won but in Seattle, the mayor said the walkout of 60,000 workers was evidence of Bolshevik influence. Public alarm over the event hurt the purpose of unions throughout the US. Also, an AFL campaign to organize steelworkers had charges of radicalism against William Z. Foster, its leader, who joined the Socialists in 1900 and became a Communist later. Attention to Foster's radicalism made the public aware of the common 12 hour day and seven day week of the steelworkers. In 1919, 340,000 steelworkers walked out, but the union gave up the strike four mounths later. Public opinion favored the workers when the knew about working conditions, but the strike was already over. In the same year, the majority of the Boston police striked. Governor Calvin Coolidge used the National Guard to maintain order.

Four days later, the strikers were ready to return but the police commissioner refused to take them back. Coolidge responded to Samuel Gompers' appeal for reinstatement by claiming, "There is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, any time." To add to the labor unrest, southern blacks came north to take mining jobs and Italian "scabs" also took mining jobs away from soldiers who expected to have their jobs back when they returned home. The "Bolshevik menace" was a big contributor to labor unrest. Many Americans linked the "Bolshevik menace" to the labor unrest and mob violence. Many Americans feared that the US might fall to Communism. After the strikes, such as a strike in Seattle, the nationwide steelworkers' strike, and the Boston police strike, many Americans blamed the unrest on the radical immigrants since many strikers recently immigrated from Southern and Eastern Europe. Many blamed the labor strikes and race riots on the Bolsheviks and some radicals believed that domestic troubles in America, similar to that in Russia, was a part of a world revolution.

Left-wing members of the Socialist party created the Communist and the Communist Labor parties. Many bombs arrived in post offices and other violence persisted at the time. Also, there were police raids and many radicals were being deported by the order of the Justice Department in 1919. The Bolshevik scares left a stigma on labor unions and added to the anti-union open-shop campaign ("American Plan"). Racism and xenophobia reached great heights. Socialism was popular in the areas where there were many immigrants. The flow of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe rose after the war and in 1921, the Emergency Immigration Act was passed to reduce immigration. There were also some disputes about inadequate wages, long hours, and poor working conditions.

The disputes have led to violence on several occasions. The miners joined in a union after hearing about success of miners in other parts of the country. The Matewan miners heard about other miners who went on a two month long strike and won a 27% pay increase. Under John L. Lewis as the president of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), more miners were joining the union. Another contributor to unrest in Matewan was the monopoly of the coal companies on Matewan. Instead of being a capitalistic system, the coal companies dominated the town and every aspect of the miners' lives. Miners wanted to emancipate themselves from the monopoly of the coal companies and joined the union. Miners joined the union with the risk of losing their homes and jobs. The companies responded by using Baldwin-Felts detectives to evict miners and their families from the company-owned homes. The Baldwin-Felts detectives arrived on May 19, 1920 and evicted six families and stacked their belongings outside the homes. Many people heard about the evictions and became furious.

They rushed into town with guns to confront the detectives. The mayor, Cabel Testerman, and police chief, Sid Hatfield, sided with the miners. Hatfield attempted to arrest Al Felts for evicting miners without Matewan authority. The miners and detectives faced each other. It is unknown who fired the first shot, but someone started firing and then the melee broke out. There were several deaths; seven detectives were killed, including Al and Lee Felts and two miners were killed in the battle. Also, Matewan�s mayor Cabel Testerman got shot and was dying. Angry miners followed the Battle of Matewan with events such as the march to Logan County. Hatfield eventually died 15 months later when the Baldwin-Felts detectives killed him at the McDowell county courthouse. In August 1921, approximately 5,000 miners, still angry, gathered for a protest march to Logan County. Between 1,200 and 1,300 state police, deputy sheriffs, armed guards, and others stopped the marchers at Blair Mountain, near the Boone-Logan county line. A battle went on for four days. At Governor Ephraim Morgan's request, 2,100 federal troops to Blair Mountain to stop the event.

A group of planes flew over to survey the event. To be prepared, reinforcement of Federal forces came back including a chemical warfare unit and a bomber and fighter planes. The miners eventually surrendered. About 543 people were indicted on charges, including murder, treason, and carrying guns. Union membership plummeted after 1921.

The Battle of Matewan led to the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) of 1933, which established the right to bargain collectively. The NIRA was eventually replaced by the Wagner Act that established minimum wages, shortened workdays, and improved working conditions.

�The time has come to see Matewan in perspective, the way we do Lexington and Gettysburg --- not just as an isolated incident of the tragic spilling of blood, but as a symbolic moment in a larger, broader and continuing historical struggle --- in the words of Mingo county miner J.B. Wiggins, the �struggle for freedom and liberty.� �historian David A. Corbin

No comments:

Post a Comment