William Claude Dukenfield (January 29, 1880

[1] – December 25, 1946), better known as

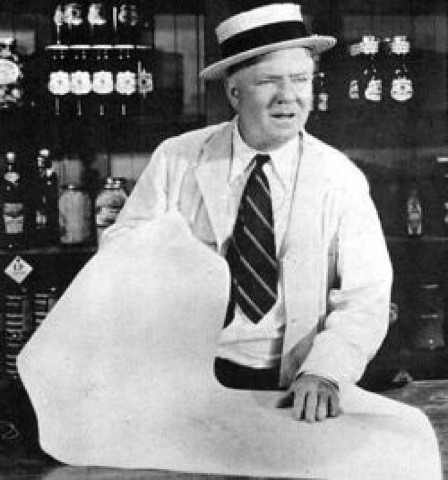

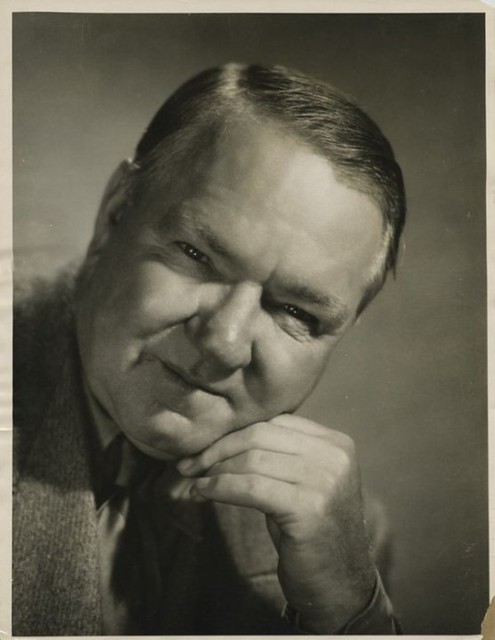

W. C. Fields, was an American

comedian, actor,

juggler and

writer.

[2] Fields was known for his comic

persona as a

misanthropic and hard-drinking

egotist who remained a sympathetic character despite his snarling contempt for dogs, children and women.

The characterization he portrayed in films and on radio was so strong it became generally identified with Fields himself. It was maintained by the movie-studio publicity departments at Fields's studios (

Paramount and

Universal) and further established by Robert Lewis Taylor's 1949 biography

W.C. Fields, His Follies and Fortunes. Beginning in 1973, with the publication of Fields's letters, photos, and personal notes in grandson Ronald Fields's book

W.C. Fields by Himself, it has been shown that Fields was married (and subsequently estranged from his wife), and he financially supported their son and loved his grandchildren.

However,

Madge Evans, a friend and actress, told a visitor in 1972 that Fields so deeply resented intrusions on his privacy by curious tourists walking up the driveway to his Los Angeles home that he would hide in the shrubs by his house and fire

BB pellets at the trespassers' legs. Several years later

Groucho Marx told a similar story on his live performance album,

An Evening with Groucho.

[edit]Biography

[edit]Early years

Fields was born William Claude Dukenfield in

Darby,

Pennsylvania. His father, James L. Dukenfield, was from an

English-

Irish Catholic family that emigrated to America from

Sheffield, England in 1854.

[3] James Dukenfield served in Company M of the 72nd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment in the

American Civil War and was wounded in 1863.

[4] Fields's mother, Kate Spangler Felton, 15 years younger than her husband, was a

Protestant of German ancestry. The 1876 Philadelphia City Directory lists James Dukenfield as a clerk. After marrying, he worked as an independent produce merchant and a part-time hotel-keeper.

[5]

Claude Dukenfield (as he was known) worked at the

Strawbridge and Clothier department store and in an oyster house, before he left home at age 18 (not 11, as many biographies have said).

[citation needed] At age 15, he had begun performing a juggling act at church and theater shows, and entered

vaudeville as a "tramp juggler" using the name W. C. Fields.

[3] He soon was traveling as "The Eccentric Juggler", and included amusing asides and increasing amounts of comedy into his act, becoming a headliner in North America and Europe. In 1906 he made his

Broadway debut in a musical comedy,

The Ham Tree.

Fields embellished stories of his youth, but his home seems to have been a reasonably happy one. His family supported his ambitions for the stage, and saw him off on the train for his first stage tour. His father visited him for two months in England, when Fields was performing there in music halls.

[3]Fields was known among his friends as "Bill".

Edgar Bergen also called him Bill in the radio shows (while

Charlie McCarthy called him many names). Fields played himself in

Never Give a Sucker an Even Break, and his "niece" called him "Uncle Bill". In one scene he introduced himself: "I'm W.C., uh, Bill Fields." When he was portrayed in films as having a son, he often named the character "Claude", after his own son. He was sometimes billed in England as "Wm. C. Fields", due to "W.C." being the British slang for a

water closet or toilet. His public use of initials was a commonplace formality of the era in which he grew up. "W.C. Fields" also fit more easily onto a marquee than "W.C. Dukenfield".

[edit]Personal life

Fields married a fellow vaudevillian, chorus girl Harriet "Hattie" Hughes, on April 8, 1900.

[6] Their son, William Claude Fields, Jr., was born on July 28, 1904.

[7] Although Fields was "an avowed atheist [who] regarded all religions with the suspicion of a seasoned con man", he yielded to Hattie's wish to have their son baptized.

[8]At the time Fields was away from Hattie on tour in England. By 1907, however, he and Hattie had separated; she had been pressing him to stop touring and settle down to a respectable trade, while he was unwilling to give up his own livelihood.

[9] Until his death, Fields continued to correspond with Hattie and voluntarily sent child-support payments.

He had another son, born on August 15, 1917, with girlfriend Bessie Poole, named William Rexford Fields Morris.

[10]Bessie was an established Ziegfeld Follies performer and met Fields while performing in New York City at the famous Amsterdam Theater. Her beauty and quick wit attracted Fields, who was the featured act from 1916 until 1922. She was killed in a bar fight several years later, leaving their son to be raised in foster care, where he acquired the surname Morris by his foster-mother. Fields sent voluntary support to young Bill in care of his foster mother until he graduated from high school, when he sent $300 as a gift.

Fields lived with

Carlotta Monti (1907–1993) after they met in 1932, and they began a relationship that lasted until his death in 1946. Monti had small roles in a couple of Fields' films, and in 1971 wrote a biography,

"W.C. Fields and Me", which was made into a motion picture at Universal Studios in 1976.

[edit]Fields and alcohol

Fields's screen character was often fond of alcohol, and this trait has become part of the Fields legend. In his younger days as a juggler, Fields himself never drank, because he didn't want to impair his functions while performing. The loneliness of his constant touring and traveling, however, compelled Fields to keep liquor on hand for fellow performers, so he could invite them to his dressing room for companionship and cocktails. Only then did Fields cultivate a fondness for alcohol.

Fields expressed his feelings to

Gloria Jean (playing his niece) in

Never Give a Sucker an Even Break: "I was in love with a beautiful blonde once, dear. She drove me to drink. That's the one thing I am indebted to her for." Equally memorable was a line in the 1940 film

My Little Chickadee: "Once, on a trek through Afghanistan, we lost our corkscrew...and were forced to live on food and water for several days!" The oft-repeated anecdote that Fields once claimed he never drank water "because fish fornicate in it" (other rumours state Fields used a far ruder description) is unsubstantiated.

On movie sets, Fields kept handy a

vacuum flask of mixed

martinis, which he referred to as his "pineapple juice". While filming

Tales of Manhattan, a prankster switched the contents of the flask, filling it with actual pineapple juice. Upon discovering the prank, Fields was heard to yell, "Who put pineapple juice in my pineapple juice?!"

[11]In 1936 Fields became gravely ill, his health worsened by his heavy drinking. Fields's film series came to a halt while he recovered; he made one last film for Paramount,

The Big Broadcast of 1938. The comedian's troublesome behavior kept other producers away, and Fields was professionally idle until he made his debut on radio. By then Fields was very sick and suffering from

delirium tremens.

[edit]On stage

[edit]Vaudeville

Fields started as a juggler in

vaudeville, appearing in the makeup of a genteel "tramp" with a scruffy beard and shabby tuxedo. He juggled cigar boxes, hats, and a variety of other objects in what appears to have been a unique and fresh act, parts of which are reproduced in some of his films. Fields confined his act to pantomime so that he could play international theaters. Fields toured several continents and became a world-class juggler and an international star. He worked bits of juggling into many of his films. A good portion of his act is contained in

The Old Fashioned Way.

[edit]Broadway

Back in America, Fields found that he could get more laughs by adding dialogue to his routines. His trademark mumbling patter and sarcastic asides were developed during this time. (According to the

A&E Biography program about Fields (1994), when he was young his mother would sit with him on the front steps and mumble comments about the passersby.)

He soon starred on

Broadway in

Florenz Ziegfeld's

Ziegfeld Follies revues. There he delighted audiences with a wild

pool skit, complete with bizarrely shaped cues and a custom-built table used for a number of hilarious gags and surprising

trick shots. His pool game is reproduced, at least in part, in some of his films, notably in

Six of a Kind (1934).

He starred in multiple editions of the

Follies and in the Broadway musical comedy

Poppy, where he perfected his persona as a colorful small-time

confidence man.

[edit]Silent era

Fields starred in a couple of short comedies, filmed in New York in 1915. His stage commitments prevented him from doing more movie work until 1924. He reprised his

Poppy role in a silent-film adaptation, retitled

Sally of the Sawdust (1925) and directed by

D.W. Griffith. Following this, he starred in

It's The Old Army Game (1926) which featured his friend

Louise Brooks, later to become a screen legend for her role in

G.W. Pabst's

Pandora's Box in Germany. The film included a silent version of the porch sequence which would one day be expanded in the sound film

It's a Gift (1934). Fields wore a scruffy-looking, clip-on mustache in virtually all of his silent films, discarding it only after his first sound feature film,

Her Majesty Love, his only

Warner Brothers production.

[edit]At Paramount

Fields made four short subjects for comedy pioneer

Mack Sennett in 1932 and 1933, distributed through

Paramount Pictures. During this period, Paramount began featuring Fields in full-length comedies, and by 1934 he was a major movie star. It was for one of the films of this period (

International House) that outtakes of one scene (Fields, and two other actors) allegedly recorded the only moving image record of the

1933 Long Beach earthquake. This footage was later revealed to have been faked as a publicity stunt for the movie.

He often contributed to the scripts of his films, under unusual

pseudonyms such as the seemingly prosaic "Charles

Bogle", which appeared on most of his films in the 1930s; "Otis Criblecoblis", which contains an embedded

homophone for "scribble"; and "Mahatma Kane Jeeves", a play on

mahatma and on a phrase an aristocrat might use when about to leave the house: "My hat, my cane,

Jeeves". In features such as

It's a Gift and

Man on the Flying Trapeze, he is reported to have written or improvised more or less all of his own dialogue and material, leaving story structure to other writers.

In his films, he often played hustlers such as carnival barkers and

card sharps, spinning yarns and distracting his marks. He had an affection for unlikely names and many of his characters bore them. Some examples are:

- "Larson E. [read "Larceny"] Whipsnade" (You Can't Cheat an Honest Man);

- "Egbert Sousé" [pronounced 'soo-ZAY', but pointing toward a synonym for a 'drunk'] (The Bank Dick);

- "Ambrose Wolfinger" (Man on the Flying Trapeze); and,

- "The Great McGonigle" (The Old-Fashioned Way).

The carnival fraud was not the only character Fields played. He was also fond of casting himself as the victim: a hapless householder constantly under the thumb of his shrewish wife and/or mother-in-law. His 1934 classic

It's a Gift included his stage sketch of trying to escape his nagging family by sleeping on the back porch, and being bedeviled by noisy neighbors and traveling salesmen. That film, along with films such as

You're Telling Me! and

Man on the Flying Trapeze, ended happily with a windfall profit that restored his standing in his screen families.

Although lacking formal education, he was well read and a lifelong admirer of author

Charles Dickens, whose characters' unusual names inspired Fields to do likewise for his various characters. He achieved one of his career ambitions by playing the character Mr. Micawber, in

MGM's

David Copperfield in 1935. In 1936, Fields re-created his signature stage role in

Poppy for

Paramount Pictures.

[edit]Supporting players

Fields had a small cadre of supporting players that he employed in several films:

- Kathleen Howard, as a nagging wife or antagonist.

- Alison Skipworth, as his wife (although 16 years his senior), usually in a supportive role rather than the stereotypical nag.

- Grady Sutton, typically as a country bumpkin type, as either a foil or an antagonist to Field's character.

- Baby LeRoy, a pre-school child fond of playing pranks on Fields' characters.

- Tammany Young, as a dim-witted, not intentionally harmful assistant; appeared in seven Fields films until his sudden death from heart failure in 1936.

- Bill Wolfe, a gaunt looking character, usually a Fields foil.

- Jan Duggan, an oldish woman (actually about Fields' age) who played small roles as a widow type. It was about her character that Fields said in The Old Fashioned Way, "She's all dressed up like a well-kept grave."

- Franklin Pangborn, a fussy, ubiquitous character actor of the period who played in several Fields films, most memorably as J. Pinkerton Snoopington in The Bank Dick.

- Elise Cavanna, whose on-screen interplay with Fields was compared (The Art of W.C. Fields 1967 by William K. Everson) to that between Groucho Marx andMargaret Dumont

[edit]At Universal

- Fields: "Was I in here last night, and did I spend a $20 bill?"

- Shemp: "Yeah."

- Fields: "Oh boy, what a load that is off my mind... I thought I'd lost it!"

Fields often fought with studio producers, directors, and writers over the content of his films. He was determined to make a movie his way, with his own script and staging and his own choice of supporting players. Universal finally gave him the chance, and the resulting film,

Never Give a Sucker an Even Break, (1941) is a masterpiece of absurd humor in which Fields appeared as himself, "The Great Man". Universal's singing star

Gloria Jean played opposite Fields, and his old cronies

Leon Errol and

Franklin Pangborn served as his comic foils. But the film Fields delivered was so surreal Universal recut and reshot parts of it and then quietly released both the film and Fields.

Sucker turned out to be his last starring film. By then he was much heavier and less mobile than he had been at the peak of his film career during 1934–1935, when he was reasonably fit and trim.

Fields completed a scene for the

20th Century Fox film

Tales of Manhattan, (1942) in which he played an eccentric professor hired by

Margaret Dumont to give a temperance lecture to a gathering of high society swells. This scene was cut from the film before release, supposedly due to running time. It was discovered in the vaults at Fox in the mid 1990s and was included in the video and DVD releases of the movie.

[edit]On radio

While Fields was inactive in films due to extended illness, he recorded a short speech for a radio broadcast. His familiar, snide drawl registered so well with listeners that he quickly became a popular guest on network radio shows.

[12] One of his funniest routines had him trading insults with

Edgar Bergen's dummy

Charlie McCarthy on

The Chase and Sanborn Hour.

Fields would twit Charlie about his being made of wood:

- Fields: "Tell me, Charles, is it true your father was a gate-leg table?"

- McCarthy: "If it is, your father was under it!"

When Fields would refer to McCarthy as a "woodpecker's pin-up boy" or a "termite's flophouse," Charlie would fire back at Fields about his drinking:

- McCarthy: "Is it true, Mr. Fields, that when you stood on the corner of Hollywood and Vine, 43 cars waited for your nose to change to green?"

- Bergen: "Why, Bill, I thought you didn't like children."

- Fields: "Oh, not at all, Edgar, I love children. I can remember when, with my own little unsteady legs, I toddled from room to room."

- McCarthy: "When was that, last night?"

Thanks to radio, Fields reached an even wider audience than before, and he was soon in demand for films again.

[edit]Final years

Fields occasionally entertained guests at his home. Generally, Fields fraternized with other actors, directors, and writers who shared his fondness for good company and good liquor.

John Barrymore,

Gregory La Cava, and

Gene Fowler were a few of his intimates.

Anthony Quinn and his wife

Katherine DeMille(daughter of Hollywood director

Cecil B. DeMille) were visiting Fields one afternoon when the Quinns' two-year-old son, Christopher, drowned in Fields’s lily pond. Fields was greatly distraught by this incident, and brooded about it for months.

[13]In the 1994

Biography TV show, his 1941 co-star

Gloria Jean described how she would visit his house from time to time, and they would talk. Gloria Jean found Fields to be kind and gentle in real life, and believed that Fields yearned for the kind of family he lacked when he was a child. The show also reported that Fields eventually reconciled with his long estranged wife and son, and enjoyed playing with his grandchildren.

With a presidential election looming in 1940, Fields toyed with the idea of lampooning political campaign speeches. He wrote to vice-presidential candidate

Henry A. Wallace, intending to glean comedy material from Wallace’s speeches, but when Wallace responded with a warm, personal fan letter to Fields, the comedian decided against skewering Wallace. Instead, Fields wrote a book entitled

Fields for President, humorous essays in the form of a campaign speech. Dodd, Mead and Company published it in 1940 but declined to reprint it at the time. It did not sell well, mostly because people were confused as to whether it was meant to be taken seriously. Dodd, Mead reprinted it in 1971 when Fields was seen as an anti-establishment figure. The 1940 edition includes illustrations by

Otto Soglow; the 1971 reprint is illustrated with photographs of Fields.

Fields's film career slowed down considerably in the 1940s. His illnesses confined him to brief guest-star appearances in other people's films. An extended sequence in

20th Century Fox's

Tales of Manhattan (1942) was cut from the original release of the film; it was later reinstated for some home video releases. He performed his famous billiard-table routine one more time on camera, for

Follow the Boys, an all-star entertainment revue for the Armed Forces. (Despite the charitable nature of the movie, Fields was paid $15,000 for his appearance, and he was never able to perform in person for the armed services.) In

Song Of The Open Road (1944) Fields juggled for a few moments, remarking, "This used to be my racket". His last film, the musical revue

Sensations of 1945, was released in late 1944.

He also guested occasionally on radio as late as 1946, often with Edgar Bergen, and just before his death that same year he recorded a spoken-word album, delivering his comic "Temperance Lecture" and "The Day I Drank A Glass Of Water" at

Les Paul's studio, in which Paul had just installed his new multi-track recorder. The session was arranged by Paul's old Army pal Bill Morrow, a friend he had in common with Fields. Fields's vision had deteriorated so much that he read his lines from large-print cue cards. It was W. C. Fields's last performance.

Fields spent his last weeks in a hospital, where a friend stopped by for a visit and caught Fields reading the

Bible. When asked why, Fields replied, "I'm checking for loopholes." Fields died in 1946 (from an alcohol-related stomach

hemorrhage) on the holiday he claimed to despise:

Christmas Day.

[14] As documented in

W.C. Fields and Me (the memoir of Carlotta Monti, published in 1971 and made into a

1976 film of the same name starring

Rod Steiger), he died at Las Encinas Sanatorium,

Pasadena, California, a bungalow-type sanitarium where, as he lay in bed dying, his longtime and final love,

Carlotta Monti, went outside and turned the hose onto the roof, so as to allow Fields to hear for one last time his favorite sound—the sound of falling rain. According to the documentary

W.C. Fields Straight Up,

[15] his death occurred in this way: he winked and smiled at a nurse, put a finger to his lips, and died. Fields was 66, and had been a patient for 22 months. His funeral took place on January 2, 1947, in Glendale, CA.

Fields was cremated and his ashes interred in the

Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery, in

Glendale, California. There have been stories that he wanted his grave marker to read either "On the whole, I would rather be in Philadelphia", his home town, or "All in all, I would rather be in Philadelphia", both of which are similar to a line he used in

My Little Chickadee: "I'd like to see Paris before I die...Philadelphia would do!" In the same film, he made a point of referencing "Philadelphia

cream cheese"; whether he knew of the actual

J. L. Kraft Foods product is unknown. Given his fondness for words, maybe he just liked the sound of his own home town's name. This rumor has also morphed into "I would rather be

here than in Philadelphia". The anecdote that Fields often remarked, "Philadelphia, wonderful town, spent a week there one night" is unsubstantiated. It is also said that Fields wanted "I'd rather be in Philadelphia" on his gravestone because of the old vaudeville joke among comedians, "I would rather be dead than play Philadelphia". Whatever his actual wishes might have been, the interment marker for his ashes merely bears his stage name and the years of his birth and his death. The genesis of the line as originally phrased can be found in a 1925 article in

Vanity Fair entitled "A Group of Artists Write Their Own Epitaphs." The mock-epitaph for Fields reads "Here Lies / W.C. Fields / I Would Rather Be Living in Philadelphia."

[16][edit]Unrealized film projects

W. C. Fields was the original choice for the title role in the 1939 version of

The Wizard of Oz. One rumor was that he believed the role was too small. Another alleged that he was asking too much money: his asking price was $100,000, while MGM offered $75,000. However, his agent asserted that Fields rejected the role because he wanted to devote his time to writing

You Can't Cheat an Honest Man.

No comments:

Post a Comment